James Earl Jones: More Than Just a Magnificent Voice

Magnificent. This term encapsulates the talents of an unparalleled American actor whose work spans both theater and cinema, a monumental presence known for voicing Darth Vader, commanding stages like Broadway with his portrayal of Troy Maxson in "F fences," and consistently delivering mesmerizing performances—from playing the Moor of Venice to portraying the boxer in "The Great White Hope" and the hermit-like wise man in "Field of Dreams."

Has there ever been a performance by James Earl Jones that didn't provide proof that giants roam the Earth?

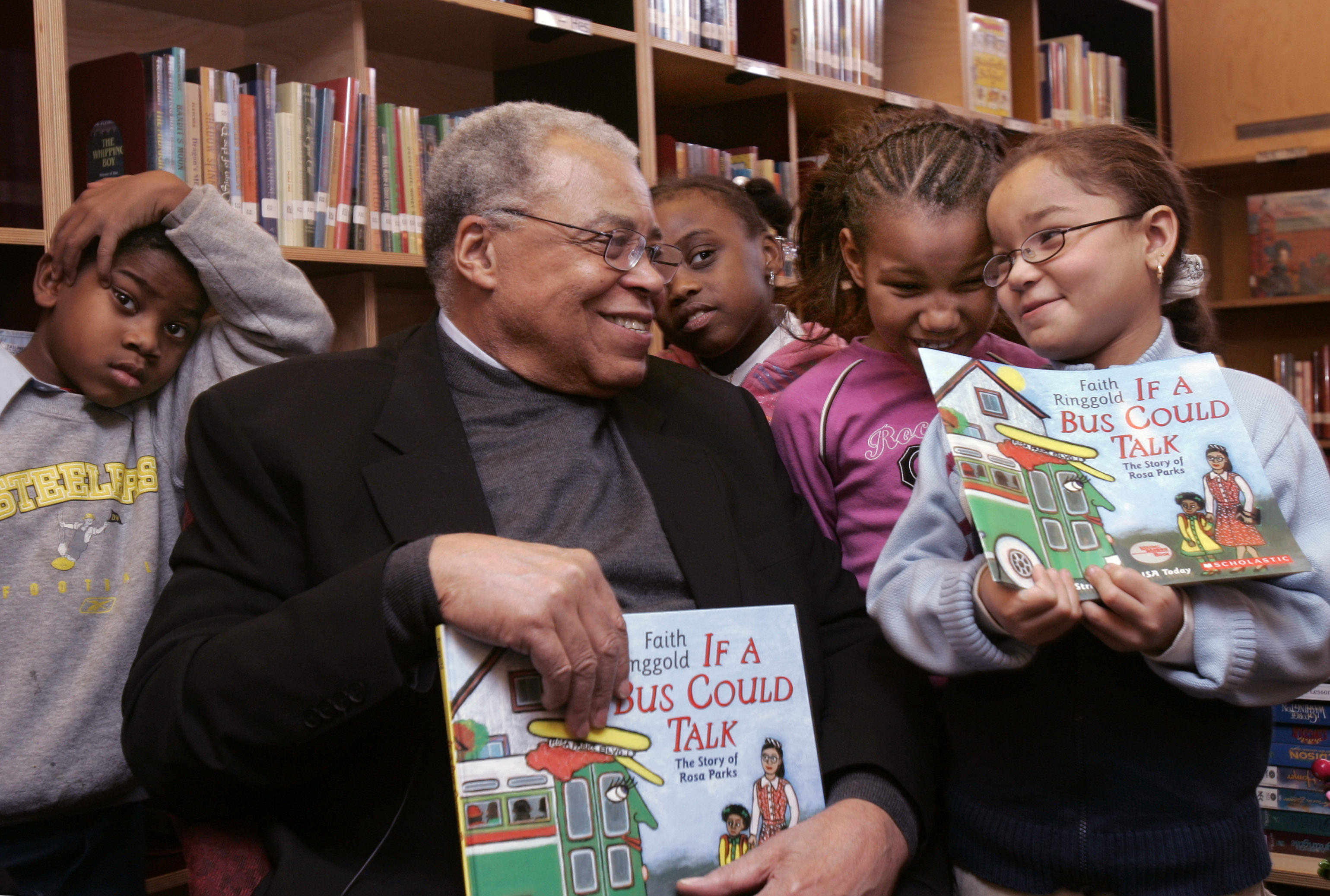

His innate ability expressed itself satisfactorily through various decades so frequently that Jones, who passed away on Monday at the age of 93, , became a go-to source for assignments that registered as consummately authoritative. Disney needed a regal sound for Mufasa, the reigning monarch of Pride Rock, in the original animated “The Lion King”? Ted Turner required the voice of a basso deity to intone his network’s lead-in and sign-off, “This is CNN”? Directors wanted a personality that radiated command, in films such as “Clear and Present Danger” and “The Hunt for Red October”? Whether it was a kingship or an admiralty, Jones seemed born to play it.

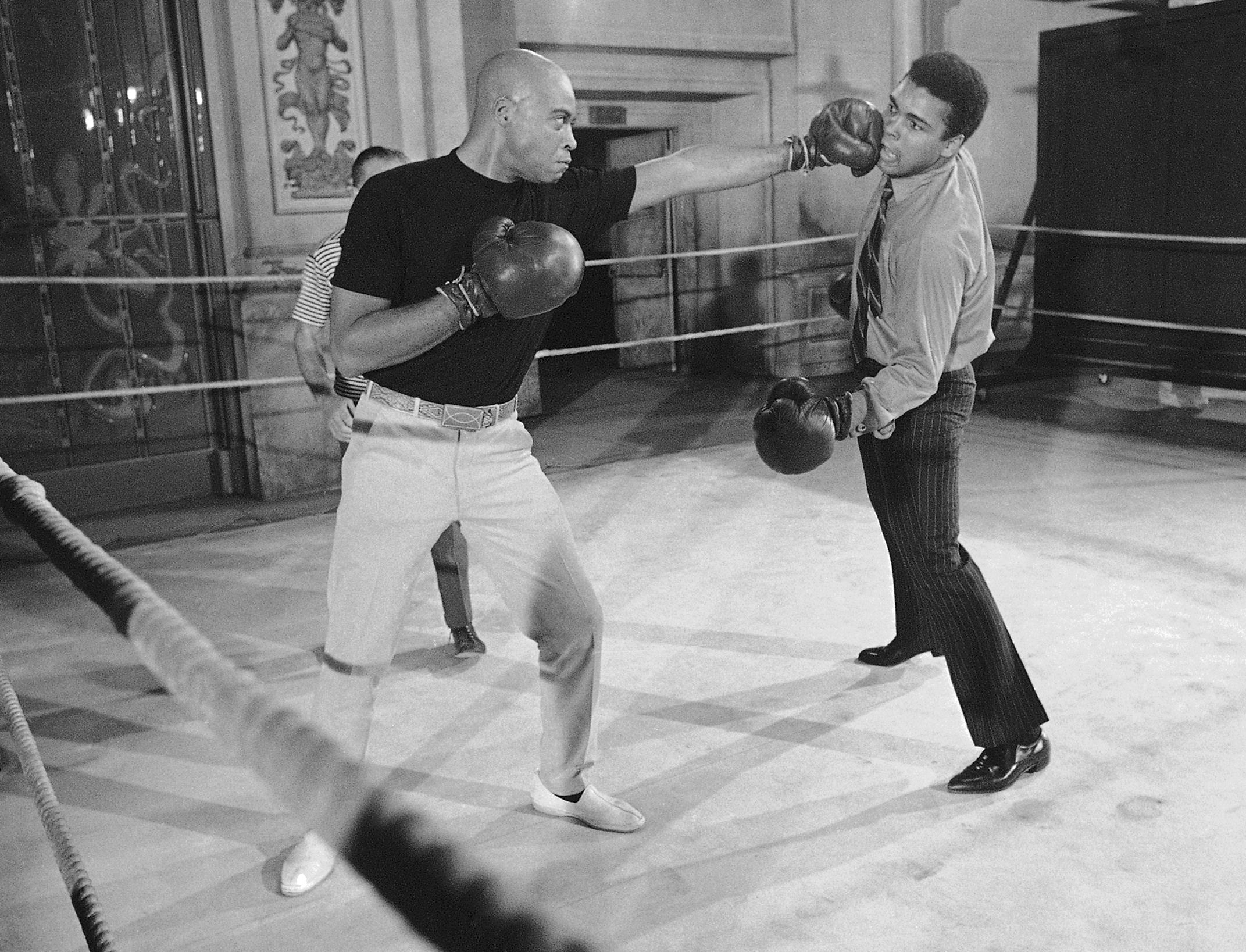

Of course, Jones's influence went far beyond what his singing talents brought him. He gained prominence in 1967 when he performed at Washington's Arena Stage in the groundbreaking world premiere of "The Great White Hope." This was Howard Sackler’s acclaimed drama destined for Broadway and later awarded with a Pulitzer Prize. The story delves into the racial discrimination faced by Jack Johnson—referred to as Jack Jefferson in the script—the inaugural African American boxer who rose to be the heavyweight champion.

Still, As he mentioned to me in 2002 when he received the Kennedy Center Honors. Although he didn't see himself as a symbol of identity politics, he simply considered himself an actor who also happened to be Black. He found it amusing when fellow actors started shaving their heads, inspired by his "Great White Hope" appearance. When asked about this during an interview in a Georgetown hotel room, he stated, "I dislike the term 'race.' Being Black or having an ethnicity is clear enough; however, race creates divisions among people."

Maybe it was the challenges he encountered during his upbringing in Mississippi and Michigan with his maternal grandparents that fostered within him an unshakable confidence, one that defied easy categorization. Surprisingly, considering his life story, he struggled severely with stammering as a young boy—so much so that he considered himself almost silent until age 14. It wasn’t until high school, when he delved into the poetic beauty of literary works, that he discovered his true voice. "Through poetry, I learned to articulate another tongue—one filled with rounded Rs: from Longfellow, Shakespeare, to Chaucer," he shared.

It appeared that his sanctuary lay within the intellectual universality of the authors he grew fond of. It comes as no surprise then that one of the most compelling roles of his acting journey was bestowed upon him by the eminent 20th-century theatrical virtuoso, August Wilson. "Fences" stands out as Wilson's most cherished drama, with Troy—a disgruntled garbage collector plagued by remorse and overwhelmed by disillusionment—emerging as the writer's most intricately developed tragic protagonist.

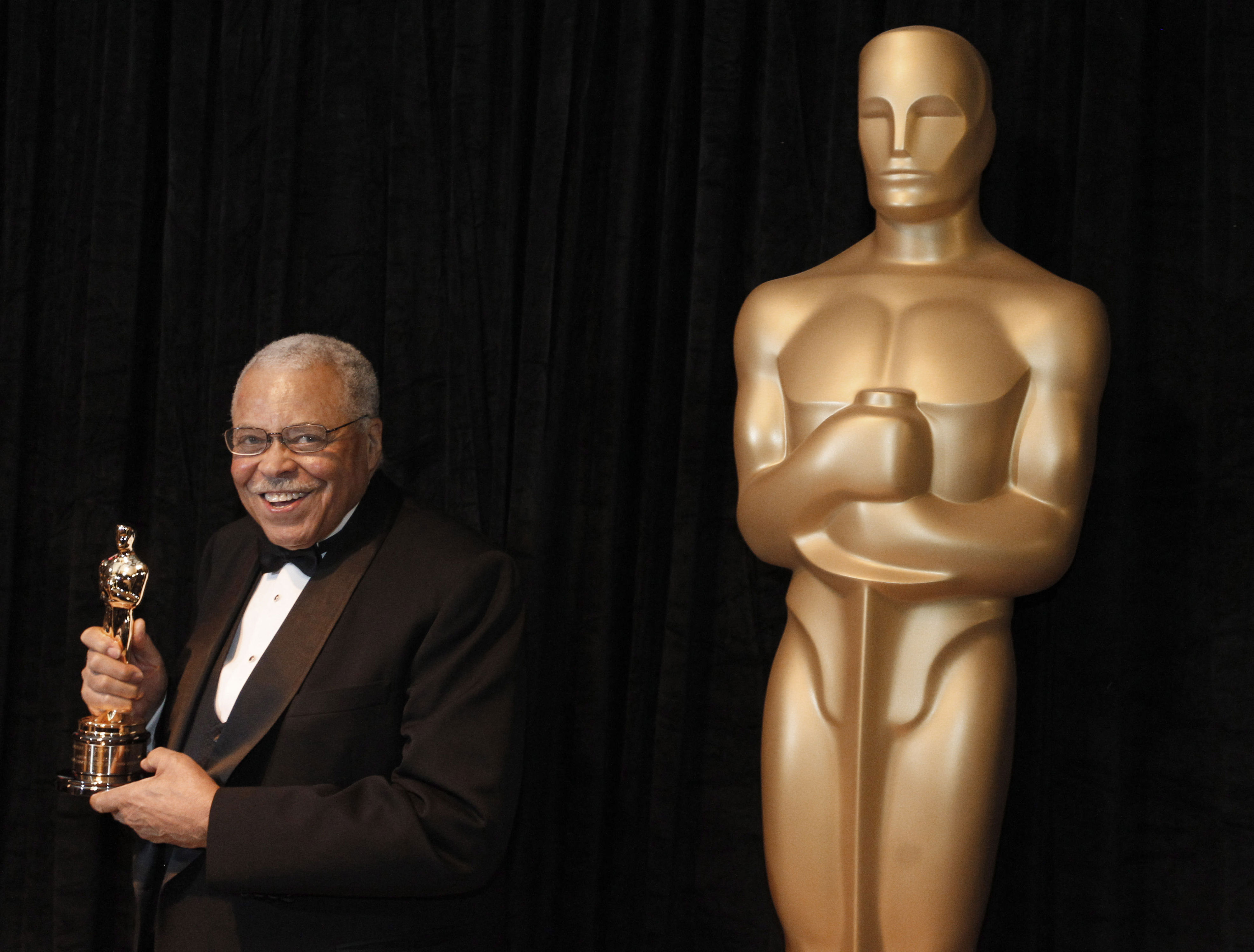

Jones delivered an outstanding performance in the 1987 original Broadway production, which was helmed by director Lloyd Richards. This role secured Jones his second Tony Award for Best Actor; "The Great White Hope" had previously won him his first. Most importantly, this portrayal showcased the versatility of Jones’s acting abilities. I recall distinctly the climactic scene where, compelled to face the enormity of his failings as both a man and a father, Troy swings a baseball bat at his son, Corey, portrayed by Courtney B. Vance.

The situation was too much for Jones to bear. He implored Wilson to clarify that Troy would never genuinely swing the bat at Corey. Faced with Wilson’s hesitation, he collaborated with Richards to devise a physical signal indicating that Troy had no intention of following through and hitting anyone. "At minimum," Jones shared with me, "I could exit the scene assured that I wouldn’t end up killing my own child."

The admission highlighted an actor who heavily immersed himself in the personal aspects of a intricate character. However, he showed somewhat lesser dedication when it came to negotiating contracts. Jones remembered that during the making of the initial Star Wars film — which went on to gross approximately $775 million at the global box office — He received $7,000 for it. Furthermore, the Darth Vader recording session went on for just 2½ hours.

Twenty-one Broadway productions, along with numerous other plays, movies, television shows, and voice-over work make for an impressive resumé—a record that reads as a comprehensive overview of American entertainment spanning six decades. However, meeting him personally revealed a genuinely unpretentious individual behind the creation of these formidable characters. Even at our farewell, he modestly requested to take a photo with me.

“A Shakespearean stage director once told him, ‘Avoid getting consumed by portraying a monarch; instead, play a mere human,’” and this advice left an indelible mark on James Earl Jones.”

Comments

Post a Comment