The Hidden Ties Between Britain and the World's Most Enigmatic Ancient Civilizations

New archaeological research is revealing that, more than a thousand years before Britain became part of the Roman Empire, it was part of an extraordinary Mediterranean-based trading network.

Research conducted by archaeologists from five European nations indicates that approximately 3,300 years ago, the western Mediterranean island of Sardinia began transforming into a significant trade hub. This development ultimately connected locations such as Britain, Scandinavia, Spain, and Portugal in the west with areas including present-day Turkey, Syria, Israel, Cyprus, and Crete in the eastern region.

A sequence of groundbreaking findings is uncovering, for the very first time, the extraordinary contribution made by this island—one of the planet’s most enigmatic ancient societies, referred to by archaeologists as the Nuragic civilization.

And it is showing the remarkable way in which Britain seems to have contributed to that civilization's development.

It's long been known that Sardinia's Nuragic culture had Bronze Age Europe's most impressive architecture as well as equally remarkable art - but research over recent years has begun to reveal that it also became Europe's first Mediterranean-wide maritime and mercantile power.

The island (a series of chiefdoms) was rich in copper ore - which helped turn it into a Bronze Age mercantile and economic superpower (because copper was one of the two key ingredients needed to make high quality bronze, which was far stronger than copper on its own).

But the second key ingredient, needed to make high quality bronze, was tin - and one of the best sources of tin in the ancient world was Cornwall. Tin played a crucial role in human history - because it enabled the production of really strong manufactured goods and its acquisition usually necessitated and promoted long distance trade.

Recent scientific research has revealed that Cornish tin was being delivered, probably by Sardinian or Sardinian-connected merchants, to what are now Israel and Turkey.

Moreover, an investigation into a shipwreck near the Devon coastline uncovered that a Bronze Age vessel, which was transporting Cornish tin ingots as exports, also carried goods originating from Sardinia or Spain. It seems that the English Channel functioned as a major trade route during the Bronze Age, facilitating the movement of Mediterranean copper ingots and Cornish tin ingots to regions such as Scandinavia, while simultaneously enabling the transport of Danish amber to locations including Britain, Ireland, Spain, and the Mediterranean.

Moreover, an increasing amount of evidence indicates that at the core of this Bronze Age global commerce network was the enigmatic Nuragic civilization of Sardinia.

As a consequence of this trade, all segments of the network experienced growth—and recent archaeological digs have uncovered a Bronze Age settlement at what may be one of the most probable landing points on Cornwall’s side of the sea route, St. Michael's Mount close to Penzance.

On the Italian island of Sardinia, its significance as perhaps the leading center for trade during the Bronze Age contributed greatly to the emergence of an exceptional civilization.

A minimum of 10,000 prestigious stone structures were erected—some reaching heights of up to 30 meters. Over time, numerous such prehistoric edifices evolved into extensive Bronze Age fortresses, encompassing areas as large as 3000 square meters and fortified with massive walls extending for about 400 meters, bolstered by as many as 20 towers. Approximately 7000 of these ancient constructions remain intact today—including several of the biggest ones—which exemplify Europe’s earliest advanced monumental stonework architecture. These architectural marvels include intricately designed passageways supported by archways, projecting parapets, intricate mechanisms for gathering and storing water, colossal wells, and expansive chambers boasting soaring vaulted ceilings measuring upwards of 12 meters in height.

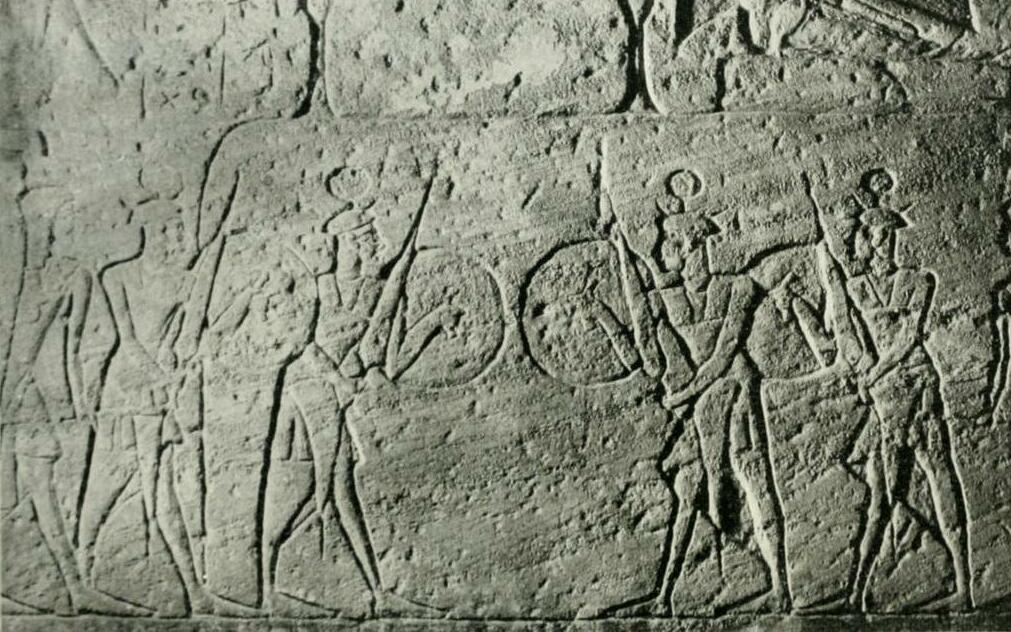

The civilization had an arguably lesser-known yet significant impact on historical development. Beyond their indirect and direct contributions to enhancing the economies of Bronze Age Britain and Scandinavia among others, there is evidence suggesting that pirates from Sardinia launched multiple attacks against Egypt and territories that now constitute modern-day Israel. Furthermore, at least one Egyptian Pharaoh was so impressed with these warriors’ combat skills that he enlisted them as part of his own elite guard.

The Nuragic people from Sardinia might have set up a minor settlement in present-day northern Israel, as well as initiated trade outposts in Sicily, Crete, and Cyprus. Archaeological digs on these three islands have unearthed Nuragic ceramics, particularly items used for dining purposes.

The Bronze Age inhabitants of Sardinia likely played a direct or indirect role in the transportation of Cornish tin, Danish amber, as well as numerous other items from Spain, Portugal, and the broader Mediterranean region. They facilitated trade routes connecting these raw materials' origins with various consumers stretching across Europe’s Atlantic coast all the way to the Middle East.

It remains unclear whether Sardinian traders established direct commerce with Britain or Scandinavia. Additionally, it’s uncertain if seafarers from Cornwall, France, or the Iberian Peninsula charted Atlantic sea routes connecting northern Europe to Portugal. Furthermore, certain goods might have been conveyed from the English Channel area to the Mediterranean through the French river network.

All the new research suggests that Sardinia itself acted as the major trading hub - with British, Scandinavian and Iberian raw materials and products (including tin, copper and amber) being shipped to Sardinia for transhipment to points further east like Crete, Cyprus, Syria, Lebanon and Israel. In the other direction Sardinian and perhaps other ships are now thought to have carried Middle Eastern glass beads, Egyptian faience, Cypriot copper ingots, precious gemstones and other products to customers in the West.

In Britain, archaeologists discovered Iranian and Egyptian beads, Scandinavian amber artifacts, Aegean metalworks, Cypriot and Spanish copper ingots, as well as Sicilian razors. These items suggest they must have been transported by sea from their origins.

The amber artifacts were probably sourced directly from Denmark; however, many of the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean merchandise likely reached Britain through trading centers in Sardinia and additional outposts in Portugal or southwestern Spain (possibly even encompassing Huelva, located roughly 100 miles northwest of Gibraltar). Recent metalwork studies indicate that tin originating from Atlantic Europe—presumably Cornwall—was conveyed to and utilized in Sardinia.

The Nuragic civilization in Sardinia was among the earliest significant centers for trade across both the Mediterranean and the European Atlantic coast. It also surpassed much of the surrounding area in technological advancements and agricultural practices.

Recent archaeological explorations have shown that they domesticated the native wild grapes of the island instead of bringing grape seeds from Middle Eastern cultivators—enabling them to create their distinctive wine, which continues to be made on the island even now.

The Nuragic or pre-Nuragic inhabitants of Sardinia developed their own method of cheesemaking (produced using the stomachs of recently slain young goats and employing the creature’s enzymes for fermentation)—a technique from those ancient times is still crafted on the island today (the sole location in Europe where this early cheesemaking custom endures).

What's more, archaeobotanical analysis carried out at a Sardinian university, Cagliari, has now revealed that Sardinia was also the first place in the western Mediterranean to start using another important food resource - melons (which prior to the Nuragic civilization had been a purely eastern Mediterranean culinary product).

The Bronze Age inhabitants of Sardinia enjoyed a sophisticated cuisine characterized by wine consumption and the inclusion of exotic fruits. Their religious practices were likely influenced by similar customs encountered through extensive trade and exploration journeys.

Icnonographic and additional evidence indicates that, much like ancient Crete, they seem to have possessed a 'human-bull' worship practice (possibly akin to the Cretan devotion represented by the well-known legend of the Minotaur).

The Nuragic fascination with navigation is evident in the latter stage of their artistic development—they were the ancient Bronze Age society that created an overwhelming number of bronze and ceramic ship sculptures. So far, archaeologists have discovered 160 bronze models along with countless pottery versions.

Archaeologists haven't definitively determined just how far these explorers ventured into uncharted territories. These individuals might very well be considered among Europe’s earliest major adventurers. It has been confirmed that they arrived at Western Asia, and it is highly likely that they engaged in direct trade along the Atlantic shores of Spain and Portugal, as well as having indirect dealings with regions such as Britain and Scandinavia.

However, there is intriguing evidence suggesting that ancient Sardinians might have traveled to Britain—a peculiar and mystifying rock-carved tomb exists in northern Scotland, specifically on the island of Hoy within the Orkney archipelago. This structure stands out as the sole example of its kind discovered in Britain thus far; interestingly, its closest resemblance can be found in Sardinia.

Archaeological and various scientific studies aimed at enhancing our comprehension of Sardinian Bronze Age trading networks have been conducted across eight institutions: Durham University in the UK, the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, Aarhus University in Denmark, along with local universities such as those in Cagliari and Sassari within Sardinia itself. Additionally, researchers from Freiburg and Bochum Universities in Germany, both renowned centers for study, alongside the Curt Engelhorn Centre for Archaeometry located in Mannheim, Germany, have also contributed significantly to this field of inquiry.

"The significance of Bronze Age Sardinia within the broader prehistoric context of Europe and the Mediterranean area is just starting to gain proper recognition among archaeologists in recent times,” stated Dr. Serena Sabatini, an authority on Bronze Age trade systems and associate professor of archaeology at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden.

"Metalwork, ceramics, and various artifacts found at numerous locations throughout the Mediterranean and even farther afield demonstrate the extensive geographic reach of the Nuragic network. Additionally, growing evidence indicates that besides the Mediterranean, regions along Europe’s Atlantic coastline—such as Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavia—also supplied trade goods to this network," explained Dr. Sabatini.

The Independent stands out as the globe’s premier source of unbiased journalism, offering worldwide news, insights, and examination tailored for those with an independent mindset. This publication has attracted a vast international audience composed of people who appreciate our reliable perspective and dedication to fostering constructive transformation. Today more than ever, fulfilling our purpose of driving change forward remains crucial.

Comments

Post a Comment